by Tony Indovina

September 2020

This multifaceted House History story is about a house in the Murdoch Farms neighborhood of Squirrel Hill owned by a young friend of mine, Noam Gilboa. His house is in the block of Aylesboro Avenue near Schenley Park. The research technique used was a comprehensive search of newspaper articles from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette Archives website. Research was thoroughly and skillfully gathered by SHHS member Lauren Winkler. Because this method is somewhat of a shotgun approach, it will not uncover the more precise chain-of-ownership information that would result from following steps outlined in Co-President Wayne Bossinger’s June SHHS newsletter article entitled “Researching Your House’s History.” Perhaps another chapter of this house’s history can be documented with this type of formal deed search. Noam believes his house was originally owned by a member of the Murdoch family, and that it was once moved from its original location. The information we found through news articles, however, is decidedly more serendipitous. In all, twenty-two newspaper reports were uncovered from the house address and six from the society pages. Of the newspaper reports, four were profoundly disturbing.

Basic house ownership information over the years is revealed through another eight news articles, of sales notices and ads for sale that embellish. Our house was described in various articles as a Victorian brick, from 10 to 12 rooms and three baths, with parquet floors, “atmospheric” spaces and a view. Those advertising sale prices, mostly from the 1990s through the early 2000s, reveal a somewhat sluggish housing market, with asking prices increased and reduced through the early ‘90s. After being listed for more than 20 times its 1920 sales price, it was ultimately purchased by our present owner for less.

All the other news entries reveal stories far more interesting than sales and real estate transactions. The earliest, from 1913, is an ad for a laundress from the quaint old phone number 2528-J Schenley. We turn ahead now to when the Tunnell family resided in the house, during what may have been its longest period of ownership by one family—from 1930 to the last news report of their address from 1956. Through these articles, we are able to glimpse social life from another era of wealthy families in early twentieth-century Pittsburgh.

High Society

This charming part of the story begins with the debutante announcement for the older of the two Tunnell sisters, Miss Helen Louise Tunnell, while a guest in Palm Beach, Florida. Palm Beach figures prominently in other society page stories, as we learn it is the home of the girls’ aunt, Mrs. Peyton Van Rensselaer. During news of one of these visits, the sisters were reported to be guests at the “exclusive” Bath and Tennis Club in Palm Beach, with other guests including “Prince George of Russia and Lord Deices of England.” Eventually, we learn of younger sister Miss Helen Louise Tunnell’s introduction to Baltimore society, as she makes her “bow with the sub-debs.” Baltimore, we learn, was the former home of her parents. Both sisters graduated from The Winchester School for Girls, the younger daughter going on to Miss Wright’s School in Bryn Mawr and the older becoming a member of the Pittsburgh Junior League. Wedding announcements for both appeared later, including one marrying a Harvard graduate. Another wedding announcement appeared in a Ft. Worth newspaper, also reporting that the sisters’ maternal grandparents were very prominent in the early development of Ft. Worth. The last of the entries for the Tunnell family reports that the aunt, Mrs. Peyton Van Rensselaer, passed away on a visit to the house on Aylesboro, and that before living in Palm Beach, she had been a prominent member of Philadelphia society.

And Then the Unthinkable Happens

Stories uncovered from a newspaper search of a house’s history might contrast wildly. To illustrate this, we go back to four articles appearing in Pittsburgh newspapers one and two days after the night of June 2, 1919. This quiet block of Aylesboro Avenue by Schenley Park was literally rocked as part of a nationally coordinated anarchist bombing event occurring almost simultaneously in eight cities, from Boston to Washington, D.C., and Pittsburgh. As reported later, it was 11:35 p.m. Monday night when a bomb placed under the porch of a house on Aylesboro, owned by Burton J. Cassady, general manager of the paint department of the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company, tore the porch off the house and ripped through the first floor, causing considerable damage.

Houses on either side sustained somewhat less costly damage. One was the residence of the intended target, Judge W. H. Thompson of the U.S. District Court. The other was the house of our story, then owned by F. B. Lincoln, Vice-President of the Pittsburgh Railroad and Coal Company. The estimate of damage there, reported to be about $2,000, included replacement of all house windows. One news source stated that “not one pane was left intact,” which would have included the curved glass windows in the house’s beautiful turret. In all, four houses were damaged in the neighborhood, three on Aylesboro and one on Northumberland to the rear of the one bombed. About the same time, a second bomb in Pittsburgh went off seven miles away in the Esplen neighborhood of Sheraden. Two houses there were damaged and again, the bomb was left at the wrong address. A Pittsburgh district immigration officer, who lived across the street from where the bomb was placed, was the intended target. A few days later, news reports went beyond the horror of the actual bombings to reveal some of the human stories from that night. Miraculously, with families asleep upstairs, no one was injured in either of the Pittsburgh bombings. In Squirrel Hill, 15-month-old Richard Cassady was sleeping upstairs in the house bombed when a twenty-pound stone from “our” house next door flew through his bedroom window. The stone came to rest in a doll’s toy crib, three feet from where the child lay sleeping. And from our house, there was the news report of “the champion sound sleeper of the world.” Sixteen-year old Frederic Lincoln was thrown from his bed by the explosion and had to be roused by his parents, unharmed but sound asleep. The bomb used in Squirrel Hill was determined to have been a ten-inch-long, three-inch-in-diameter wrought iron device, packed with dynamite and TNT, a particularly powerful combination. Across the country, bombs used were reported to be upwards of 25 pounds. It was not uncommon during these attacks for bombs to be left at wrong addresses, as the anarchists were believed to be out-of-towners who weren’t familiar with the addresses of their intended targets. And nationally, there were as many anarchists killed by these bombs as bystanders. It was later reported that no individuals targeted anywhere across the country that night were killed. In the days following the incident in Squirrel Hill, there was much local outcry by residents of the well-to-do neighborhood about why Pittsburgh police were not on their beats during the evening of the bombing.

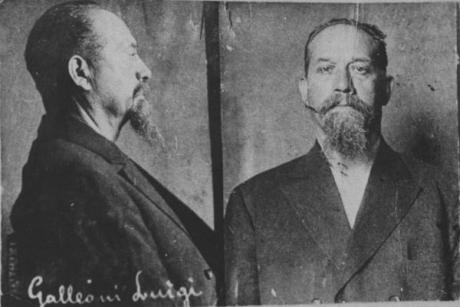

Footnote to House History Story: The suspects in all these bombings, from April to June 1919, came to be known as Galleanists, followers of a man named Luigi Galleani. He came to the United States in 1901 and settled in Vermont, where he published a radical newspaper called The Subversive Chronicle. Galleani also published booklets on bomb-making. Though never actually implicated in any of the anarchists’ activities, he was eventually deported in June 1919. According to the Time Magazine publication source below, Galleani’s followers were an amorphous group of “mostly disenfranchised young men” who were largely self-radicalized during the difficult period following World War I. They were not bound to any one ideology or leader. Their one shared belief may have been that terrorism against existing institutions would trigger a populist revolt. Their targets, as in Pittsburgh, were government officials who posed the threat of imprisoning or deporting them. As copied from methods of the Italian Black Hand, they would leave notes forewarning their action. In Squirrel Hill and elsewhere that night, bombs were left with copies of a pink flyer titled “Plain Words,” a manifesto ending with the statement, “We will destroy to rid the world of your tyrannical institutions.” The atmosphere of fear that was generated led to a harsh crackdown and treatment of many foreigners and immigrants during this time, particularly Eastern and Southern Europeans. In Pittsburgh, the bombings were following by a raid on the local downtown headquarters of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), representing Eastern European immigrant steel workers. These workers were targeted in part because they had become radicalized and organized during the boom of World War I steel production. Those gathered up were later released, as no charges could be made. Nationwide, about 10,000 immigrants were eventually arrested, 3,500 detained, and 550 eventually deported. No real relationship existed between these anarchist activities and the earlier Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Nonetheless, as reported in a Time Magazine publication, it became customary during this period to lump all such activity together under the name “Socialism,” which during this time first became a “dirty word” to discredit any leftist ideology.

Credits and Sources

Thanks to Noam Gilboa, homeowner on Aylesboro Avenue, for permission to write his House History story.

Thanks to Lauren Winkler, SHHS member, for providing a comprehensive list of news articles from Newspapers.com. Anyone interested in obtaining her services to do a news search of their house (for a fee) can send an inquiry to the SHHS, either by contacting us through our website or by sending an email to sqhillhist@shhsoc.org, with the subject “News Search.”

Baltimore Sun, 11/24/1935.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 06/23/1937.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 02/05/1956; 04/11/1993; 05/16/1993; 09/12/1993; 05/22/1994; 07/12/2003.

The Pittsburgh Press, 05/01.1913; 05/19/1920; 01/03/1930; 06/13/1932; 01/25/1933.

Brown, Ryan C. Pittsburgh and the Great Steel Strike of 1919. The History Press, 09/09/2019.

Gulliver, Katrina. “A Century Ago, May Day Brought Anarchist Bombs to Mailboxes—And Helped Transform American Politics.” Time Magazine publication. 05/01/2019.

Wikipedia.org/Galleanists

Wikipedia.org/1919 United States anarchist bombing